Most adults, especially in the Anglo-sphere, do not believe they can learn a second language. In my humble opinion, this is absolutely a bunch of baloney!

I am forced to reject the idea that it is difficult for an adult to learn another language well simply because their brains are “old” or “not as absorbent as a child’s” because this would mean that all my dreams of being a polyglot super agent will never come true as I was not fortunate enough to live in a dual-language environment or have multi-lingual parents.

Adults feel that kids just “pick things up” and “learn so quickly,” and that our grown-up brains are just too slow, too unreceptive to language by adulthood. But it’s simply not true.

The Myth of the Absorbent-Baby-Brain

Here’s the problem (well, a lot of the problems) with the “absorbent-brain-baby” myth, which I will henceforth refer to as ABB:

It completely disregards the exceptionally advantageous environment in which babies are raised in a language (or multiple ones)!!

I wish that I had the same kind of environment that a baby does when they’re learning their first language. First of all, babies take years to learn how to form their first sentences, despite having been talked to and coddled in that language every single day of their lives. And even then, when they become toddlers, they don’t speak all that well and their grammar isn’t great. It takes them a long time just to express simple thoughts and demands despite years of input from parents and people and things all around them. I’m not trying to trash talk babies (who do you think I am?), I’m just saying you can’t compare how you learn language with how they do.

Because babies are babies (or toddlers, whatever), their parents (who are adults) are there to guide them. Without their parents’ guidance, babies and toddlers do not grow to speak a language well (or at all!). This sounds obvious, but when you think about how much a baby or toddler is helped in gaining language ability, you have to think, “Of course the kid is good at this language! He was practically fed it!”

Parents and later teachers do this by first pointing out and talking about everything around the baby or that is going on in the surrounding environment to the baby whether or not they will reply. To boot, they also answer their own questions, so the baby can hear how to make both question and reply, with absolutely no effort whatsoever. “What’s this? It’s a bear! Do you like your bear? Yes, you do!! What’s his name? It’s Mr. Bear!”

When the baby does finally get to making sounds for themselves, all mistakes are instantly corrected. If a baby picks up a fork and says, “Spoon,” their mother is not going to say, “Yes! That’s a spoon!” or let the kid get away with calling a fork a spoon. They will say, while pointing to it, “No, that’s not a spoon! It’s a fork!” If the baby first pronounced “fork” as “ferk,” the mother would also soon correct it. –– How lucky!! The baby makes mistakes and gets corrected with full, correct sentences on the spot without being embarrassed by them. Usually the parent then nudges the baby to repeat the new or corrected word, “Can you say it? Fork! This is a fork! That is a spoon!”

Younger children also have no qualms with repeating things over and over and over, so when you correct them, they’ll repeat it, make songs about it, play games with it, whatever. And that’s because they’re in an environment that encourages them to repeat, to learn, to make mistakes, and to be corrected – not because their brains are just sucking up everything around them automatically. They’re just kids being kids, which means that they’re still learning how to be literate, talking adults, who are often burdened with social expectations and issues with their ego, et cetera et cetera.

And in their early school days, they write, read, and speak with teachers and other students for hours and hours every day. Still, when they make mistakes, they are corrected. Over time they learn not to repeat any glaring mistakes because they don’t want to be embarrassed in front of their peers (and their peers won’t let any mistakes slip by), and their teachers will make sure that mistakes or unusual expressions are brought to their attention and corrected because that’s their job.

It isn’t magic that allows kids to learn languages “quickly,” which really, as you can see, isn’t all that “quickly” in the first place. Usually if toddlers or younger school-age children pick up a second language quickly it is because they are eager to repeat things, aren’t self-conscious about their accents or vocabulary etc, and are in environments that allow for constructive learning, like where they are regularly corrected and assisted by parents or teachers or from practice via homework or other regular extracurriculars and exposure.

You are not a baby. You are an adult, with adult thoughts and perceptions.

Adults who want to learn another language will have a harder time simply because they aren’t going to be treated like babies or school-kids by other adults, but not because their brains are inherently broken or less absorbent!

If you, an adult, wants to learn another language well, you are going to have to do a couple of things to overcome this hurdle of, well, not being as lucky as a little kid to have other adults around you speaking to you whether or not you reply and correcting you when you make mistakes.

Social rules that adults live by and that kids don’t are the problem. As an adult talking to other adults, when you make a mistake, they are not going to correct you, are they? They’re going to assume from context or whatever what you mean, and it is likely that all of your mistakes are going to slip under the radar, turning them into habits without you even catching it. Even if you are corrected, you would likely not repeat the corrected sentence as a child would have been encouraged to do.

You also don’t have another adult asking you simple questions about everything around you, like “Is this Mr. Bear??” a hundred times so you can get used to it, but instead they’re asking you normal adult questions like, “How is your work going?” If they did ask you questions like a baby, there’s a chance you’d be offended (because you’re not a baby) or embarrassed that you couldn’t reply well, or because you were corrected for something simple. Again, it’s not your brain that’s at fault – it’s society, your environment, and your adult brain that is already wired to think complex thoughts in a particular language, not speak baby talk to someone who wants to speak adult talk.

That all being said, it’s not impossible for you to learn another language if you want to. You just have to know how to hack your learning environment to imitate that of a baby’s.

I’ve been studying Japanese for a bunch of years now, took and passed the N1 (the highest Japanese language test), and now work as a translator who also teaches English (in both English and Japanese) to basically every age. Now, I’m working on German (self-study, in Japan) because it sounds cool and I dig it – and because I want to prove that you don’t need to live in a country or be a baby in order to learn to speak a language well.

I want to share with you some techniques that I’m using now with German and had used with Japanese so that you can overcome the ABB hurdle and learn that language you’ve always wanted to. Here are my 8.

Super 8 Tips for Learning a Language (Even With Your Adult Brain) Today!

- Consistency! Regularity! Routine!!

- Engage yourself when listening, watching, reading!!

- Use multiple books and resources!

- Stay in your lane!

- Handwrite, scribble, and repeat to retain more!

- Go back to what you like for inspiration!

- Utilize teachers/instructors/speaking partners fully!!

- Test yourself regularly – write notes & memos!

1. Consistency! Regularity! Routine!

Babies have years of input before they spit anything out. You don’t want to spend that much time learning how to make simple sentences, but you can’t skip the “immersion” phase of learning. You need to make time every day to actively (that’s a key word – ACTIVELY) expose yourself to the language. Read it, listen to it, study your textbook or an old section of it, review your notes, anything.

This can’t be passive exposure either. Passive exposure is reading, watching, listening, or *studying* where you’re not breaking down words in your head, looking up unfamiliar words, translating as you read (both to and from the target language), etc. For example, when you decide to watch a French TV show but aren’t paying attention to the sentences, vocabulary, and checking whether or not you understand at intervals, you may be passively watching but you’re definitely not actively learning.

Exposing yourself regularly helps create that “input/exposure” period that babies have. At minimum, I study German for 25 minutes a day (I set a Pomodoro timer app on my phone or computer) and on days when I have more time I study for about an hour. I don’t overdo it because I don’t want to overcommit, overwhelm myself, or end up skipping days because I’m too busy to make time. Anyone can make 25 minutes a day, and more often than not, once you get into the groove of 25 minutes, you end up doing more.

If you break your routine, you find yourself having to go back to review simple vocabulary and grammar before progressing. Having the routine establishes more “input” and exposure that will make finding your new language voice easier and kind of ease-in difficult grammar (like pesky prepositions) because you see them being used more frequently, again, like a baby would.

2) Engage yourself when listening, watching, reading!!

I mentioned this in #1, but I hear this a lot with my Japanese students – they say they listen to English songs but can’t understand them, try to watch English movies but have no idea what they’re saying, or say that they can watch and listen but can’t explain what’s going on in English!

This is because they’re not doing any active engagement with the material. Babies and kids are forced to do active engagement because otherwise they can’t communicate their needs, like having to pee or wanting to eat something in particular.

Just as well, “immersion learning” is a myth! You, neither as an adult or child, will not just “pick up” language merely by being around it unless you’re actively trying to. Babies are luckier for sure, but they’re also trying to understand things because they have needs and wants and no way to express them that we understand, unless they imitate everything their parents say.

For you, the adult learner, with everything you hear, you have to ask yourself, “Did I understand that? Can I repeat it in that same way, at that same speed?” Everything you see, “Can I understand that? Could I write that sentence? Could I ask someone about it in that language?” You have to look up words you don’t know, put them in your face whenever you can, and ask yourself what you do know – mostly because you don’t have a foreign language fairy godmother who will do it for you.

And because you’re an adult learner who is probably doing self-study, you need to make those things you’re reading and listening be your teacher, your “parent.” You have to repeat what they say or write it down over and over again until they figuratively “don’t have to correct you anymore,” or you’ll end up repeating the same bad grammar, vocab, or expressions over and over.

For Videos: Pay for Netflix or a streaming service that offers material in the target language with subtitles. You absolutely need subtitles in both your language (so, English) and the target language. This is because you’re going to have a hard time figuring out exactly what is being said in the video and have to do a lot of guess work with spelling those words you heard but don’t recognize and need to look up. With subtitles, you can just write it down or open up a new tab, look it up, and know it instantly.

You should watch the video once with English subtitles to get the gist, then the following times in that target language’s subtitles, and go through it little by little, checking what you’ve heard to the subtitles, repeating over and over what is being said, and picking words to study that you hear often or would like to use yourself. You should watch the video multiple times and double check that you understand what’s going on by toggling the English subtitles on and off and testing what you’ve heard by turning all subtitles off.

For Music: Download or read the lyrics of a song you like as you’re listening to it! Not just once, either, but every single time you can. Pay attention to what you hear and what lyrics are written. Look up words you don’t know so that whenever you hear the song, you can understand and be exposed to them.

For Books / Written Materials: Pick content that you like, not what you *need* to know. Don’t be afraid to pick an easy children’s book (they’re better to start with anyway) and if you can, pick a book or material that you are already familiar with in English. Go page-by-page. Highlight and look up words you don’t know. If there are a lot of words you don’t know, look them up, read the page over and over until you don’t need a dictionary or your notes to understand. Then you can progress to the next page (and every time you start a new page, re-read the ones you’ve already done as review).

Active learning takes time, but it is rewarding. Imagine, being able to understand and talk about an entire episode of a TV show in a target language without English subtitles! Or having read and understood the pages of a book, or a newspaper/magazine article, entirely in the new language? This sense of accomplishment is what you should be striving for, and once you feel it, you won’t want to quit.

3) Use multiple books & resources!

I have a library of Japanese textbooks. I did a lot of self-teaching and found that each book had its own strengths and weaknesses – some were good at explaining grammar, others vocabulary, others only certain vocabulary or grammar – and I realized that there is no such thing as the perfect textbook. You should not rely on one single source for your language learning. It will limit your scope of the language and make it difficult for you to figure out your learning style.

When I started with German, I was using three different primary sources at the same time:

- German: How to Speak and Write It

- Langenscheit Sprachkurs Deutsch: Bild für Bild

- Sprachlern Comic: Halb sieben vor dem kino

Why three? Well, you didn’t learn everything about English from one person did you? Everyone has their own unique way of seeing and thinking about the world – the same goes for textbooks and how they teach you.

I used each of them little by little, progressing in each at the same rate as the other. Because they’re all beginner’s textbooks, they covered about the same content but in slightly different ways. I like studying the different explanations and testing what I know with the variety of practice problems. Also, having multiple resources adds to your retention of the content by building complexity in your head and more visual aids to refer to when you’re recalling a particular word or grammar.

I also suggest:

- listening to podcasts suited to your level

- playing language games suited to your level via apps/your computer

- changing the language of your phone/email/browser etc. if you’re ready

- reading books suited to your level

Perhaps you can guess what the next rule is, given the bold text of the last suggestions…

4) Stay in your lane!

By “lane,” I mean “level.” Don’t push yourself to do more difficult grammar or try to listen to news podcasts and read business-level textbooks and so on just because you think that’s where you should be. You should be working slowly from the ground up, gaining confidence and a solid foundation in the basics that allows you to ask questions, answer questions, and understand.

Don’t be embarrassed to play basic word games, read simplified books or even children’s books, or watch shows or programs aimed at kids or beginner learners. This is how everyone starts, and it will do you no good to skip it. In fact, if you hastily run through the basics trying to get to higher levels, you’ll end up frustrated and discouraged when you don’t understand most of it.

I used to get Japanese adults who would ask me to teach them private lesson-style. They said that they couldn’t speak English at all or that their levels were little more than elementary, which I equate with just spitting out words and hoping context will put them together.

They were not ready for private lessons because they didn’t have enough vocabulary or grammar knowledge to make any sort of conversation, even simple Q&A like “What did you do today?” “I went shopping.” “What did you buy?” “I bought some clothes.” Can you ask someone else what they do every day? Can you give any details, like what you eat for breakfast and how you go to work? You have to have some foresight as to how the conversation will go before jumping in, or you’re going to be staring at the other person instead of talking.

This may discourage someone and make them think that they will never gain fluency, but it shouldn’t. Getting to a level of conversation takes time. It is not the first step – just remember that kids have years of input before they start conversing with their parents, so you should also have a good input /output balance as well.

You should use yourself as your first speaking partner so you can gain some confidence. Ask yourself, “What do I eat for breakfast?” and answer it in the language. Then gradually increase your sentence making and answering speed until it feels more natural. This helps you develop your new language voice, and allows you to become comfortable with the language before having to speak to a native adult speaker, especially if you’re self-conscious about speaking.

And when you feel comfortable talking to yourself, you should celebrate that! It’s huge! When you go through a chapter of your textbook or whatever and know it 100%, party!

5) Handwrite, scribble, and repeat to retain more!

I know this is the app/digital era, but there’s something about typing that makes it more difficult to retain information than handwriting – I think it’s the ease at which your fingers can move across the keyboard. Handwriting, yes, takes time. But the time it takes for you to write adds muscle memory and reference points to the image of the words in your mind.

Writing is also important because I believe the following mantra about language ability:

If you can’t write it correctly, you can’t say it correctly. If you can’t say it, you probably can’t hear it. And if you can’t read it, then you can’t understand it.

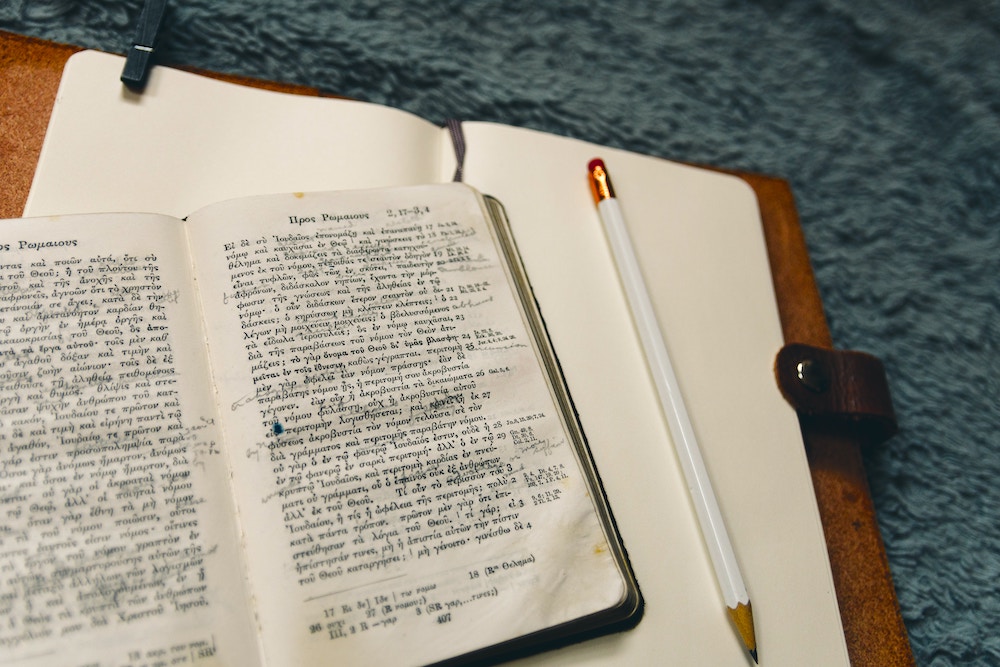

I have used tens of notebooks when I was studying Japanese intensively for jotting down vocab, copying sentences, doing practice activities, repeating sentences and vocabulary over and over… there was never a time, even when I was listening to music or watching a TV show, when I didn’t have it open and ready to catch whatever I was trying to learn or practice.

Now, I use a new notebook for German, and I’m about halfway through. Some pages are of just vocabulary, some are sentences I copied repeatedly from my textbooks, some are things I wanted to refer to, some are notes to myself about ways to remember prepositions… when I need to recall information, I often remember what page I wrote it on, what other words were written next to it, when I wrote it, and so on.

The thing is, you have to learn how to use a notebook properly to get the most out of it. What I mean is, you have to realize that it doesn’t matter what that notebook looks like, how bad or good your handwriting is, or what kind of content (vocab, grammar, mixed, whatever) is inside. What matters is that you’re using the notebook and writing whatever you can, however you damn well feel like it. Extra neat, extra sloppy, vocab on one page, sentences on the next… who cares? As long as it’s helping you, it doesn’t matter.

For me, the problem is just figuring out which notebook I wrote a particular thing in…

6) Go back to what you like for inspiration!

Getting through Japanese kanji was at times hellish. What got me through that was picking up a book, like the Japanese version of a manga I had read when I was a kid, and flipping through it. I always remembered how badly I wanted to know how to read Japanese.

When I hated Japanese grammar, I listened to Utada Hikaru, whose voice I loved and was dying to imitate – she speaks both English and Japanese fluently (and has the voice of an angel).

You should go back to these things while you study because they help you stay focused when the annoying parts about learning a language – having to memorize words, having to practice unfamiliar grammar, etc. – start to make you question whether or not you want to push through.

I also recommend making sure you study things that you like, not just things you *think* you should know. You can get to all the hard stuff later – but it will always be hard stuff if you don’t enjoy it.

You’ll enjoy doing “active engagement” (tip #2) if and only if you pick stuff that you actually like and are willing to watch, read, or listen to multiple times in a row, which definitely helps with retention. Think of those books and movies on repeat as your personal language parents, repeating the same thing over and over for you til you get it automatically.

7) Utilize teachers/instructors/speaking partners fully!!

When I moved to Japan, I was using a textbook I bought from my college bookstore before graduating (It was for Japanese II, the intermediate course I didn’t have time to take while I was still in school). A couple months after I worked through it and felt like I was in a good place with my language skills to practice speaking more, I looked for a Japanese teacher. I was in Japan, surrounded by native Japanese speakers, but yet I paid someone once a week via Skype to talk to me. Why?

Adults will not “baby” you and correct your errors

I did practice at shops and occasionally when I went to a bar, but I knew full well that I didn’t have to speak that well to have a basic conversation with someone. I wanted to express what I was thinking as well as possible, and knew that other adults I met out and about were a) not required to help me on my language journey b) were not trained to teach me or explain language-related things to me, even though they were fluent. I instead used those opportunities to see if what I had been practicing was easily understood or not by a native.

You should look for a teacher, and you should be willing to pay. I know that you may have friends who are willing to speak with you in the target language, but correcting and assisting someone with their language is not exactly a fun thing to do when you’re just trying to “talk” and hang out, and they may not be able to explain why some words or expressions are the way they are because it’s not their job.

They will also not be able to make time to meet you regularly unless there is some sort of incentive involved – trust me, unpaid regular meetings are meetings that do not have a long shelf life. Get a tutor and pay them.

When you pay someone to help you, you also gain some control in the lesson flow. Remember that that time is for you to practice and fine-tune your language skills in an environment where you will be corrected and encouraged to make mistakes and learn other ways to express things in the language. If you want to work on talking about your daily routine, tell your tutor or teacher that that is the theme for the day and ask them to help you make it sound good and natural.

This is something you can’t do with friends or people you meet out in bars or at work, because it’s not their job. You have to find a replacement “parent” who will make it their responsibility, even if just for an hour a week, to guide your language in the right direction.

8) Test yourself regularly – write notes & memos!

You need to test yourself and correct yourself (most importantly). Kids get corrected all the time, that’s why they end up speaking and writing their language well. If you don’t have a teacher you pay to correct you, you are going to have to correct yourself by using a different resource like a textbook or some literature (like a magazine) and make conscious efforts to not make the same mistakes again.

This is sometimes difficult for us to do because we may be embarrassed by our mistakes or realize that we make too many of them and thus requires more effort on our part to correct. In most cases, we are also a bit lazy in that we think that our mistakes our too slight to care that much about because “whoever I’m talking to will get the gist!” But your language learning goals should not be just to transmit the “gist” to another person. They should be to communicate as clearly as you can in that language what you’re actually thinking or feeling.

When speaking to others, you might get nervous and forget and it’s okay not to get caught up with each and every mistake you make, but it is important that you remember them, correct them, and make an opportunity to try again where your language is clearer. Otherwise, you will not make much progress.

If I’m out and noticing that I can’t communicate something well, that I forgot a word or something, I try to write it down as quickly as possible so I can look it up later. It’s okay to also tell the person you’re talking to to wait a moment while you jot down a memo in your phone. These are simply things we have to do because we are not at the advantage of kids and need to make our own little language world by ourselves.

In conclusion…

Foreign languages are tough, but not impossible. If you can make a concerted effort to create an environment around you, in whatever tiny or big way possible, in the target language, you will find yourself being able to understand and use it gradually and naturally over time.

Don’t forget to:

- Make it fun! If it’s starting to suck, be too difficult, or boring, refer to #6

- Don’t be discouraged when you’re not getting something. Try a new method (#3) or make the most of what you have by engaging with it and media (#2)

- The biggest key to gaining competence and confidence in a new language is #1 – consistent exposure! Babies need years of it before they can talk, but you won’t – all you need to do is make little efforts every day to add the language into your life that will snowball into big gains and natural proficiency.

And the best of luck to all ye other language learners!